I stopped looking for the romance and started looking for the logic. Here are seven frames that make up this Strasbourg alternative guide.

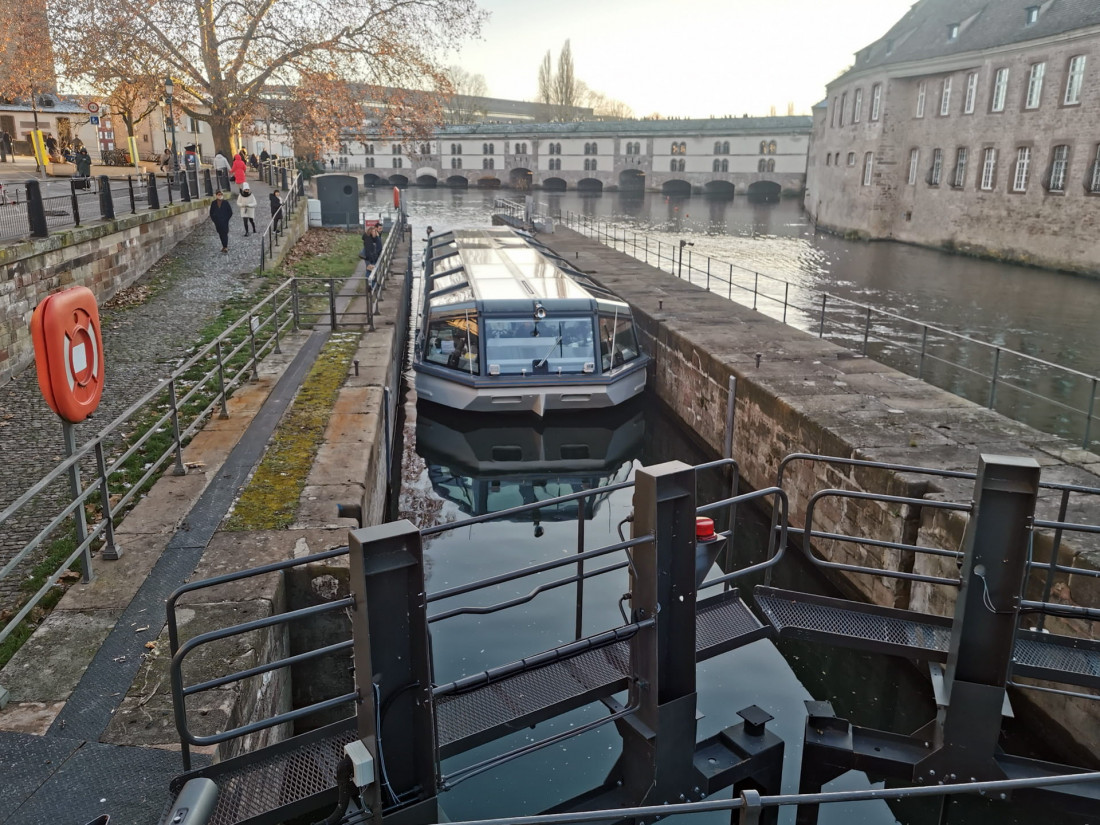

The Hydraulic Engine: Petite France

“The Engine Room.” The heavy timber and iron of the locks in Petite France remind us that this district was originally built for industry, not Instagram. The water here wasn’t a scenic backdrop; it was the power source for tanners and millers.

Tourists come here for the photos, but historically, this district was an industrial zone defined by a foul smell. It was the tanners’ quarter.

Water dictated the architecture here. The steep roofs with open lofts functioned as drying racks for wet hides, while the canals weaving through the streets served as essential tools to wash skins and power the mills.

Walking here today isn’t just a scenic stroll; it is a walk through a sanitised factory complex, the primary power system of production.

The Analog Computer: The Cathedral Clock

“A Universe in Gears.” The celestial globe in the foreground operates in a different dimension than the city outside: it tracks sidereal time, where a day lasts 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds.

Deep inside the Strasbourg Cathedral beats the city’s mechanical heart. The Astronomical Clock is not a timepiece; it is a Renaissance supercomputer.

Engineers built this machine in the 16th century to calculate the heavens with gears. It predicts eclipses, tracks planetary orbits, and calculates leap years with a mechanical precision engineered to remain accurate for centuries.

Standing before it, I realised this wasn’t an act of faith, but an act of calculation. It is the ancestor of the modern server room—a complex algorithm rendered in brass and steel.

The Exoskeleton: The Train Station

“Two Eras Colliding.” Looking up, the gap between the 19th-century stone facade (right) and the modern glass curve (left) becomes clear. This architectural bubble protects the historic structure while turning the station into a futuristic transit hub.

Strasbourg’s main railway hub, Gare de Strasbourg, is a rare case of preservation technology done right. The engineers faced a problem: how to expand a heavy, drafty 19th-century monument without destroying it.

They found the solution in a glass exoskeleton. A giant, curved climate bubble now traps the historic stone façade inside. Walking through the gap between the old stone wall and the new glass curve feels like walking inside a camera lens. It clarifies that this city uses modern engineering to protect history, rather than replace it.

The Industrial Backend: The Rhine Port

“The Industrial DNA.” This archival view of the port proves that logistics isn’t new here. Long before modern shipping containers arrived, these docks—connected by both rail and river—were already the tireless economic engine of the Rhine valley.

Most visitors end their tour at the pretty bridges of the historic centre, but the city’s real lifeline lies further east. You can spot it if you take the Batorama boat tour past the Parliament.

Here, the “system” operates at full scale. The scenery shifts from timber frames to massive gantry cranes and mountains of shipping containers.

It is the raw, unpolished logistics hub that keeps the polite city running. Watching heavy barges navigate the Rhine serves as a reality check: Strasbourg isn’t just a museum piece; it is a working engine of European trade.

Weaponised Water: Barrage Vauban

“A Strategic Current.” This medieval tower wasn’t just a lookout; it was part of a hydraulic defence line. The speed of the river here reminds you that Strasbourg’s waterways were once weaponised—capable of flooding the surrounding plains to stop an invading army.

Just past the covered bridges lies a long stone structure that looks like a gallery. Today, the panoramic terrace on its roof offers the best view of the city, but its original purpose was lethal.

The Barrage Vauban is a dam built for hydraulic warfare. In the 17th century, military engineers figured out how to use the river as a defence. By closing the arches, they could flood the lands south of the city, drowning the enemy or trapping them in mud.

This structure reminds us that in Strasbourg, the picturesque canals once served as ammunition.

Vertical Risk: The Spire

“A Skyscraper of Stone.” From this angle, the cathedral isn’t just a religious monument; it is a medieval skyscraper. You are looking at tons of pink sandstone held in place not by modern steel, but by pure geometry and iron clamps.

For 227 years, the Strasbourg Cathedral was the tallest building in the world (1647–1874). Looking up at the open-work spire, you don’t think about God; you think about gravity.

This structure seems impossible for its time—a mountain of pink stone held together by iron clamps and geometry. By all logic, it shouldn’t stand, yet it does. The spire represents the ultimate medieval ambition: to push material science to its absolute breaking point.

Builders effectively created a skyscraper before the invention of elevators or steel beams.

Frictionless Urbanism: The Tram

“The User Interface.” Sleek, silent, and efficient. The flags on the bumper reveal a unique feature of Strasbourg’s machine: this tram line doesn’t just navigate the city; it crosses the Rhine into Germany, turning an international border crossing into a frictionless commute.

The tram system here is the user interface of the city. It doesn’t rattle or screech; it glides.

In the 1990s, Strasbourg radically reconfigured its layout, pushing cars to the margins to make space for these futuristic capsules. With their massive windows and silent motors, they feel less like public transport and more like moving walkways.

This piece of the urban system functions so smoothly it becomes invisible. You don’t “take a ride”; you simply drift through the city.

Travel Notes

Strasbourg: Practical Logistics

The Verdict: Strasbourg works. That is its defining feature. Whether through the medieval gears of its clock or the silent efficiency of its modern trams, this is a city where engineering has always been the highest form of art.