When I travel, I often end up in museums dedicated to illustrators. Not in search of childhood comfort, but out of curiosity — about how someone chooses to speak to children, and what that choice reveals about their view of the adult world.

Over the years, this quiet habit has taken me to the Ilon Wikland Museum in Haapsalu and to exhibitions devoted to Tove Jansson in Helsinki. By the time I arrived in Strasbourg, visiting the Tomi Ungerer Museum felt less like a spontaneous stop and more like a continuation of a personal route — one I’ve learned to trust.

Who Tomi Ungerer was

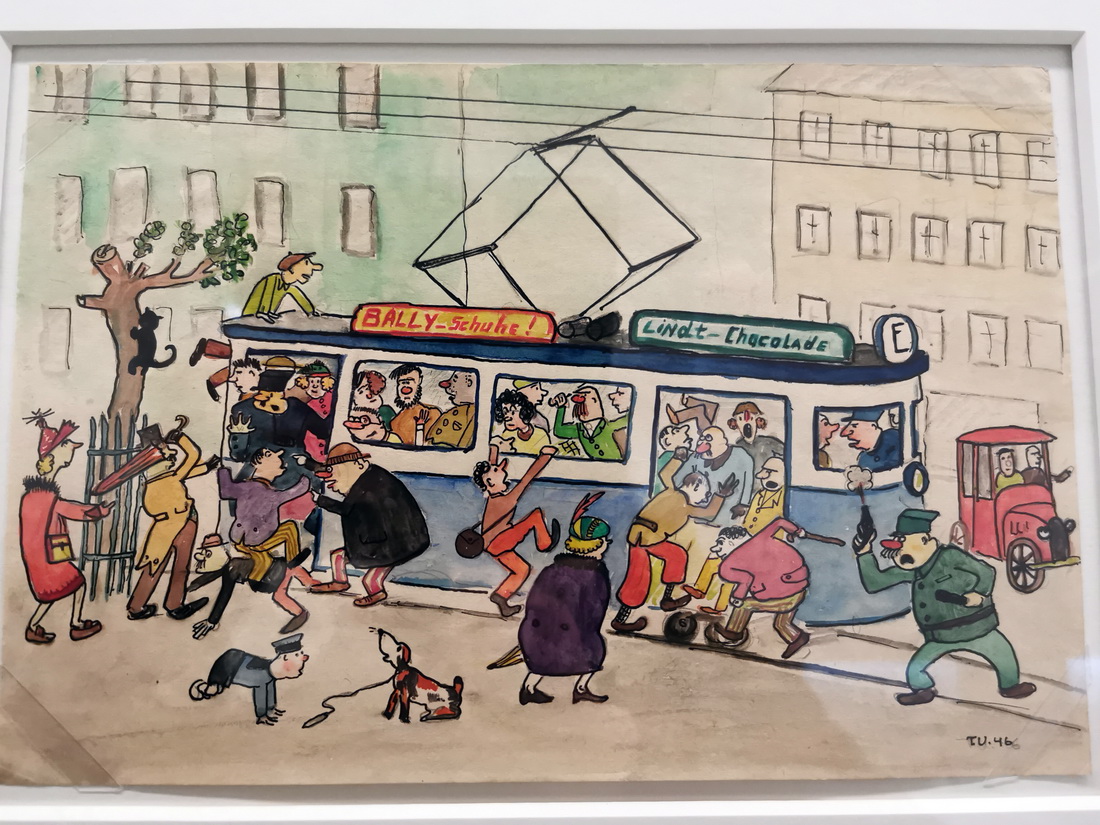

Tomi Ungerer (1931–2019) was born in Strasbourg and remained deeply shaped by it — by its borderland logic, its shifts of language and power, and its instinctive distrust of simple positions.

He is best known as an illustrator, but that label barely holds. Ungerer wrote his own books and illustrated them himself; his children’s stories appeared in French, English, German, and beyond, and many remain in print decades later.

Yet he was never only a children’s author. Alongside picture books, he produced political posters and satirical drawings — sharp, confrontational, and often deliberately uncomfortable. During his years in the United States, that work provoked controversy serious enough to affect the publication of his children’s books.

That tension was not accidental. Ungerer seemed uninterested in keeping his worlds neatly separated. The same hand that drew for children also insisted on political clarity, irony, and refusal — and never softened one for the sake of the other. It is this unresolved overlap that gives his work its lasting force.

What this museum shows — and what it doesn’t

The Musée Tomi Ungerer sets its tone quietly. Housed in an elegant 19th-century mansion near Place de la République, it feels restrained rather than theatrical — calm, measured, almost deliberately low-key.

Just as importantly, it avoids turning Ungerer into a biographical exhibit. There is no reconstructed studio, no desk frozen in time, no personal relics arranged to suggest intimacy. Personal details remain in the background, never staged as an attraction.

What fills the space instead is work: illustrations, posters, printed pages, books. You move through sequences of images rather than milestones of a life. This is a museum built around thinking through drawing — not around narrating the artist’s private story.

How it feels inside

At first, the drawings feel disarmingly familiar. Clean lines, recognisable characters, the visual language of children’s books. Nothing demands an immediate reaction.

Then the tone shifts — almost imperceptibly. You begin to notice how little Ungerer simplifies. He never cushions his ideas or explains them away. His drawings can be tender and sharply ironic at the same time, and he seems entirely uninterested in protecting his audience — children included — from complexity.

What stays with you is that refusal to talk down. Ungerer’s work assumes attention, intelligence, and a willingness to sit with contradiction. Childlike imagery coexists with adult scepticism, without apology and without smoothing the edges.

This is what makes the museum especially compelling for adult visitors. It offers no cosy nostalgia, no safe return to childhood. Instead, it presents illustration as a form of thinking — playful, precise, and at times quietly unforgiving.

A small but meaningful stop in the city

The museum sits squarely in the Neustadt (Imperial Quarter), acting as a buffer against the tourist crush. It takes only a few minutes to cross the bridge back into the medieval centre. This contrast defines the city.

If you are unsure which side of the river—the quiet Imperial grid or the busy medieval island—suits you best, I break down the logic in my guide: Choosing Your Base in Strasbourg.

But is the museum itself a must-see? Not in the checklist sense.

This is a place for readers, illustrators — and for anyone who suspects that simplicity is rarely neutral, and that the lightest line can carry far more weight than it first appears.

I couldn’t leave without a postcard with Ungerer’s work. Finding a stamp, though, turned out to be impossible.

Travel Notes

Musée Tomi Ungerer – Centre International de l’Illustration

The Strasbourg City Card gives museum discounts and includes the Batorama river tour; valid for 7 days.